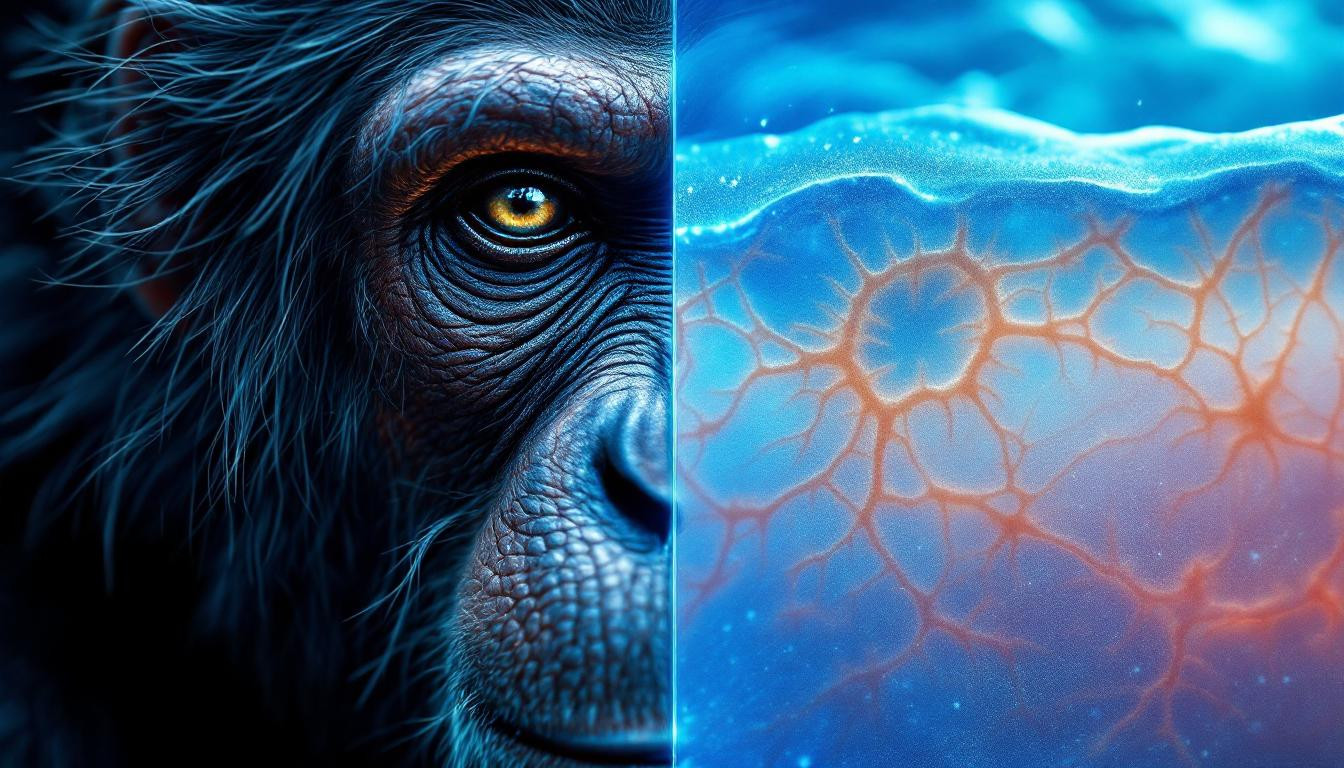

Ever wondered why we’re the “naked apes” among our primate relatives? The story behind human hairlessness reveals one of evolution’s most fascinating adaptations. While our chimpanzee cousins sport full-body fur, humans stand uniquely bare – a trait that emerged through a complex evolutionary dance of genetics, environment, and survival.

The cooling advantage: Why sweating trumped fur

When our ancestors left the shady forests for open savannas roughly 1.6 million years ago, they faced a critical challenge: avoiding overheating under the blazing sun. Thermoregulation became the primary driver behind our hair loss, allowing humans to cool efficiently through sweating.

“The human body contains between 2-5 million eccrine sweat glands capable of producing up to 12 liters of sweat daily,” explains Dr. Nina Jablonski, evolutionary biologist. “This cooling system works most effectively on relatively hairless skin, giving early humans a competitive edge during prolonged activities like hunting.”

Our genetic puzzle: The blueprint for hairlessness

Surprisingly, humans still possess the genes for a full coat of body hair – they’ve simply been deactivated through evolution. A groundbreaking 2023 study comparing 62 mammalian species identified specific genetic regions essential for hair growth that underwent changes in humans.

The KRT41P pseudogene, which helps produce keratin, lost functionality in humans around 240,000 years ago. Like a light switch flipped to “off,” this genetic change contributed significantly to our smoother appearance, as detailed in research on how experiences reshape our genetic architecture.

The big-brained connection

Our hairlessness shares an intriguing relationship with another uniquely human trait: our extraordinarily large brains. These temperature-sensitive organs benefit tremendously from efficient cooling mechanisms.

“The human brain is essentially a high-performance computer that generates significant heat,” notes Dr. Mark Pagel, evolutionary biologist. “Hair loss and sweating created the perfect cooling system that made possible our cognitive evolution, similar to how ancient tool-making reflected our developing problem-solving abilities.”

Beyond cooling: Additional theories

- Parasite reduction: Less hair means fewer places for lice and ticks to hide

- Sexual selection: Preference for less-hairy mates potentially accelerated the trend

- Social signaling: Visible skin allowed for enhanced communication through blushing and other color changes

Why we kept some hair

While losing most body hair, humans strategically maintained hair in specific areas:

- Scalp hair: Protects against direct sun exposure

- Pubic and underarm hair: Retains and disperses pheromones

- Eyebrows: Prevents sweat from entering eyes and aids in nonverbal communication

The cultural adaptation

Our ancestors’ innovative capacity played a crucial role in making hairlessness viable. Whereas other animals relied on fur for warmth, early humans developed clothing and shelter—technological solutions that functioned like detachable fur, offering protection when needed while maintaining cooling benefits.

This adaptation mirrors how we continually enhance our capabilities through technology, similar to how modern devices evolve to solve new problems or how cameras have developed to capture details invisible to the naked eye.

Capturing our evolutionary journey

Understanding our hairless heritage gives us appreciation for our bodies’ remarkable adaptations. Like how film photography captures authenticity in an increasingly digital world, tracing our evolutionary path connects us to our ancient origins.

Our relative hairlessness isn’t a deficiency but a sophisticated adaptation that helped shape who we are today—a testament to evolution’s ingenious solutions to environmental challenges. How might recognizing these adaptations change how you view your own body’s remarkable design?