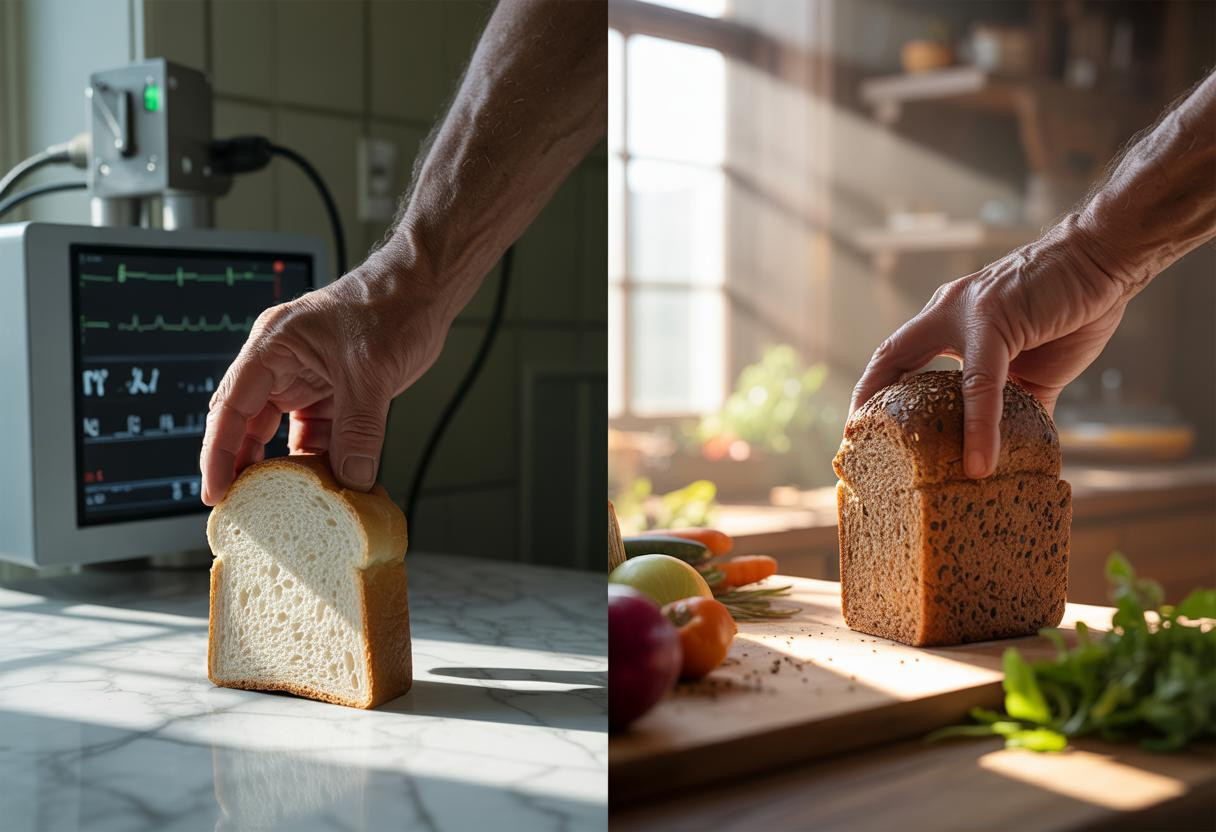

The debate around white bread consumption has reached a critical point, with Harvard medical experts now advising against its regular consumption after age 50. This warning stems from extensive research linking refined carbohydrates to various health concerns that become increasingly relevant as we age. What exactly makes white bread problematic for those in their golden years, and why are Harvard doctors taking such a firm stance?

The blood sugar rollercoaster after 50

White bread ranks high on the glycemic index, causing rapid blood sugar spikes that become more problematic with age. “After 50, our bodies become less efficient at processing carbohydrates,” explains Dr. Elizabeth Morrison, nutrition specialist at Harvard Medical School. “These repeated glucose surges can accelerate insulin resistance, potentially leading to type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular issues.”

Like filling your car with low-quality fuel, white bread provides quick energy but leaves your metabolic engine sputtering and stalling throughout the day—a particularly dangerous scenario for aging bodies.

The missing nutritional pieces in your dietary puzzle

White bread undergoes extensive processing that strips away crucial nutrients and fiber that become increasingly vital after 50. Harvard’s research indicates whole grains contain nearly four times more fiber than their refined counterparts, directly impacting healthy aging processes.

“The fiber deficit in white bread is particularly problematic for older adults,” notes Dr. Robert Chen, gastroenterologist affiliated with Harvard. “Adequate fiber intake helps maintain digestive health, manage weight, and stabilize blood sugar—all critical concerns after 50.”

The inflammation connection you can’t ignore

Harvard researchers have identified a concerning link between refined carbohydrates like white bread and inflammatory responses in the body. This chronic inflammation can exacerbate age-related conditions including arthritis, heart disease, and cognitive decline.

Studies tracking white bread consumption in adults over 50 revealed those consuming it four or more times weekly showed significantly higher inflammatory markers compared to whole grain consumers, according to emerging dietary health trends.

Smart alternatives for your daily bread

Harvard nutrition experts recommend these healthier alternatives:

- Whole grain bread with visible grains and seeds

- Sprouted grain varieties for enhanced nutrient absorption

- Sourdough bread for better digestion and blood sugar response

- Rye bread for higher fiber content

The personalized approach to bread consumption

Emerging research from Harvard suggests the impact of white bread varies significantly between individuals based on genetic factors, gut microbiome composition, and existing health conditions. This aligns with broader personalized diet approaches gaining traction in nutritional science.

I recently observed this variability firsthand when my father and uncle, both in their 60s, participated in a continuous glucose monitoring program. Despite identical diets, my father’s blood sugar spiked dramatically after white bread while my uncle showed minimal response.

Hidden dangers beyond the slice

Harvard researchers warn white bread often contains concerning additives:

- Added sugars masquerading under various names

- Preservatives with potential long-term health impacts

- Emulsifiers that may disrupt gut health

These concerns mirror broader issues with food safety and nutrition standards, particularly relevant for older adults with increased vulnerability to chemical additives.

Making the transition: practical steps forward

Rather than abruptly eliminating white bread, Harvard nutritionists recommend a gradual transition to healthier eating patterns. Begin by replacing one white bread meal weekly with a whole grain alternative, eventually establishing new habits that support longevity and vitality.

Is removing white bread after 50 really worth the effort? According to Harvard’s extensive research, absolutely. The evidence suggests this single dietary change could significantly impact your health trajectory through your 50s, 60s, and beyond—proving that sometimes, the best medicine isn’t what you add to your diet, but what you mindfully choose to leave behind.